By Patricia Hopper Patteson

When we define characters, a helpful way to talk about them is in three dimensions.

First dimension

First dimension shows the way a character looks and acts (hair, makeup, car, clothes, where she hangs out, musical choices, foods attitudes, prejudices). This is their outward identity, or their brand if you will.

First dimension outward characteristics may not always be the true character or real nature of the protagonist. Readers’ assumptions about first dimension characteristics can be deceiving and misleading .

You just have to look at Ted Bundy. There’s a movie out about him on Netflix that proves that looks can be deceiving. Bundy’s first-dimension persona was very different from his third-dimension true self. Outwardly, he was charming and articulate–a clean-cut law student with no criminal record. However, it is clear that he was a cunning deceiver with his lawyer, Polly Nelson, saying, “Ted was the very definition of heartless evil.”

If the writer doesn’t deliver all three dimensions of a character without a specific reason for doing so, then they leave this variable up to the reader to figure out for themselves.

Second dimension

Second dimension is when you start to show what’s behind the character’s outer identity– the character’s choices and behaviors that forms their identity. Many of these are driven from their backstory.

For example, a writer invents a male character who drives an expensive Cadillac to show the world he has money and power. An innocent observer, seeing the confident well-dressed man stepping out of a Cadillac, would agree with this perception. However, the writer knows the character’s background. When the character was growing up, people looked down on him and his family because they drove around in a beat-up old truck and were labeled white trash. Meanwhile, the elite of the town rode around in their Cadillacs and received respect. So, owning a Cadillac is more than just a simple desire for this character; it’s a powerful symbol of his triumph over poverty, a declaration to the world that he’s left his dirt-poor days behind.

The second-dimension characteristics is what drives the character’s choices and come from family life, scars, memories, habits, fears, weaknesses, anger, frustration, etc.

Third dimension

Third dimension has to do with choices and behaviors that have consequences–the choices that a character makes when something is at stake. This is the person we see emerge at the end of the story.

The third person dimension doesn’t necessarily have to align with the first or second dimensions.

This is where we show character growth or where the character arc comes into play. We show the heart, soul, and moral compass of the character. This comes later in a story and will show the character’s growth or change (otherwise known as the character arc).

An example would be a story about a character who has always been on the right side of good. An opportunity occurs where he/she is tempted to embezzle money without the likelihood of getting caught. The character toys with the idea of how having this money will improve his/her living circumstances—maybe they have a large debt hanging over them. The moment he/she decides to risk everything and embezzle the money… that’s when the truest aspect of the character emerges and is delivered to the reader.

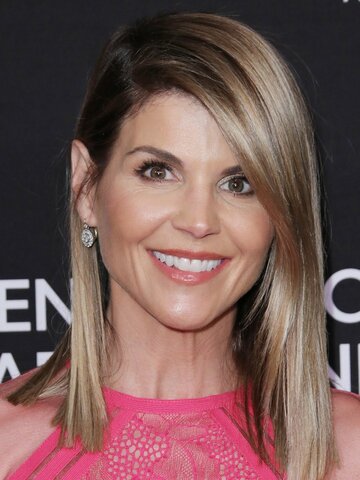

Character Study Using Dimensions: Lori Loughlin

1st dimension — wholesome, successful, stylish, charming. Gives the impression of being a good Christian with Christian values.

2nd dimension – Details about her background are sketchy. She comes from a middle-class family in NY with Christian morals, and she began modeling at age 12. She never went to college and she seems to regret this along with her husband who also never went to college. Her early modeling got her into acting and she managed to keep a squeaky-clean image all through her career, which gives a picture of a wholesome, honest person—but is she really?

3rd dimension – Like Lori, her husband didn’t go to college, but he registered. Instead, he used his college funds to start his career. Lori wanted her daughters to go to a prestigious college, despite their inability to achieve the proper scores. So she used her wealth to get them what they couldn’t manage themselves. If she had been true to her 1st and 2nd dimension self, she would have made the courageous decision to let her daughters earn their own way into college.

In fact, she was untrue to the façade of her first-dimension self of being squeaky clean and honest, and her true self was actually corrupted by her wealth and circumstances, which can lead to dire consequences. It was her 3rd dimensional persona that ended up in the public eye and ultimately defines her true self. It has nothing to do with how she wears her hair or how stylish she is, or even her second-dimension self and the fact that she never went to college.

Three Dimensions are Key

Characters are the sum of their actions and decisions motivated by their worldview and moral compass.

The sum of the character doesn’t necessarily come from childhood or how a person grows up. It is the sum of choices and behaviors and the boundaries they cross. The risks they take and the consequences their choices bring. Readers tend to love a vulnerable hero who recognizes her own weaknesses and temptations and conquers them in favor of a higher calling.

Peripheral characters

Secondary characters are usually one-dimensional, and they should be. Character development should be reserved for the main characters in your story, but that doesn’t mean your minor characters can’t be interesting. You can add an interesting tid-bit about them that is meaningful to the story. Like if the cab driver is wearing a WVU shirt and your main character is from West Virginia.

Don’t go too deep with minor characters, unless it’s relevant to the story. The reader doesn’t need to know their backstory. They should just quietly come and go on the canvas of your story. If first dimension characters make quirky decisions, then you’ll have to show their two-dimensional choices for those decisions, but always keep in mind that they are there to enhance or support your main characters.

Photo by James Coleman on Unsplash

This is a fantastic resource for anyone.